Care leavers: it is vital to hear their voices on whether a scheme is working or not

The social care system is littered with abandoned projects and wasted opportunities.

There is a tendency for public service providers to implement an innovative pilot intervention to support teenagers leaving care, only for the intervention to wither away in the face of financial pressures or the absence of managerial support.

It happens so frequently that those working in health and social care have even coined a new word to describe the process - ‘pilotitis’.

Meanwhile, the brute realities facing young people who have been looked after in the care system remain the same as they have always been. Teenagers leaving a residential children’s home or similar institutional setting are eight times more likely to have a youth justice caution or conviction.

They are also two and a half times more likely to become a young parent; four times more likely to experience mental ill health issues; and are less likely to achieve academically in school, attend higher education, or to be in employment.

So how we do improve the situation? How do we sustain some of those care leaver projects that the Department for Education (DfE) has invested in under its Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme in recent years? How do we help care providers support the transition of 18-year-old care leavers into adulthood and independence more effectively?

It is the question I have been asking myself for quite some time now, and one that a research team and I have tried to address in a number of ‘deep dives’ into three local authority projects over four years (2020-2023). The result has been an academic paper – How to Sustain Pilot Innovation in Public Services: A Case of Children’s Social Care Innovation.

Supported by funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the study allowed us to track the sustaining of innovation beyond the projects’ pilot funding of the first two years.

It also allowed to see for ourselves the malign factors that can so often lead to pilotitis: the risk averse tendencies of so many local authorities, the financial pressures that demand ‘frugal innovation’ from public service providers, and so on.

But we resisted the temptation to act like surgeons – identifying the ‘cancers’ so that we could mark the spot for knife and scalpel.

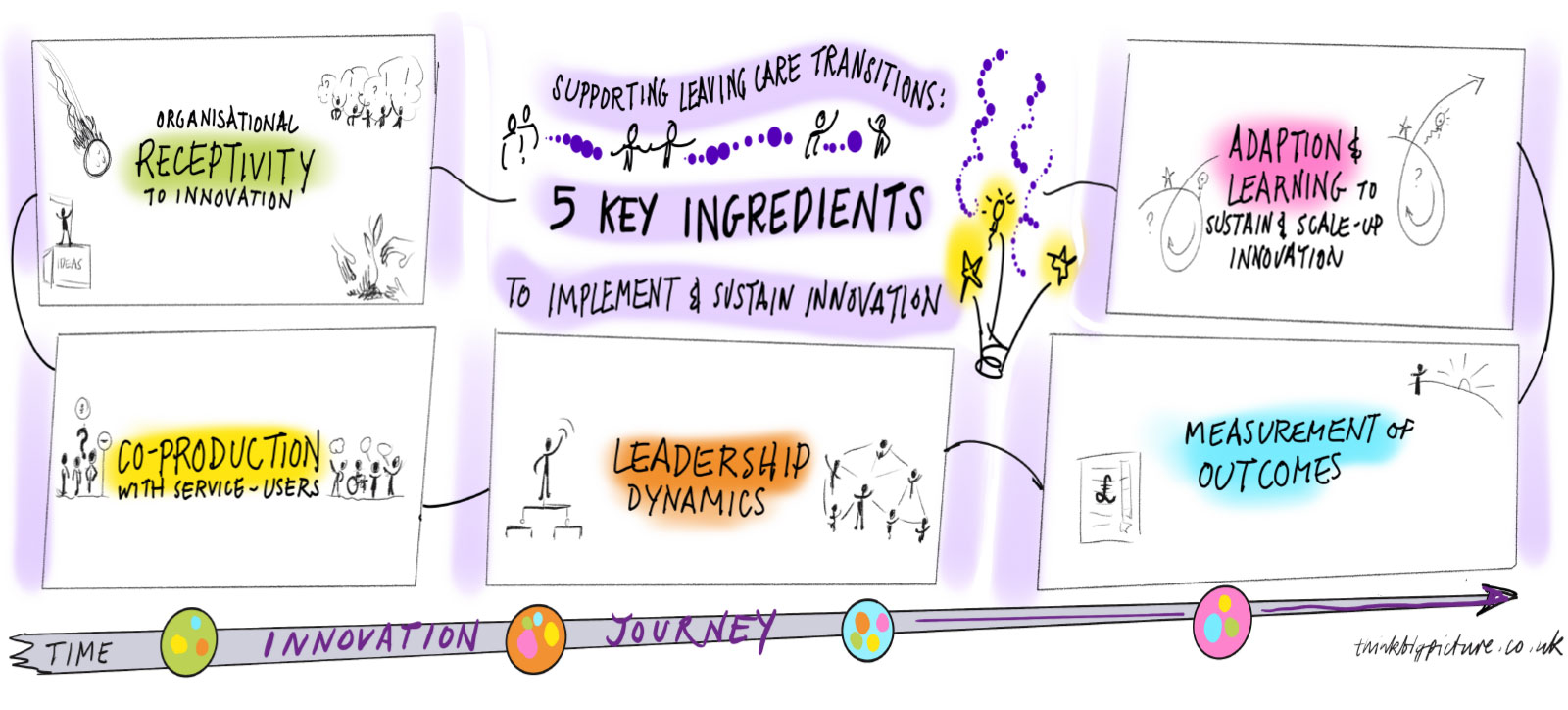

Instead, we took quite a different approach, framing social care innovation as a ‘journey’, which is not only complex and non-linear, but also involves a diverse array of stakeholders all the way from frontline professional to the service user – the care leavers themselves.

And within that framework, and using primary data gleaned from our case studies, we identified five key ingredients for sustaining innovation beyond the pilot scheme.

1 Organisational receptivity to innovation

Receptivity to innovation is really the first stage of the innovation journey – all else flows on from that. However, despite the attractiveness of the notion (we’d all like to be open to innovation, wouldn’t we?), it can be notoriously difficult to achieve.

If we consider the cash-strapped social services department in a local authority operating under severe financial pressures we can begin to understand why. Add a top-down leadership structure to the mix and we probably have an even better idea.

In a context where leadership is concentrated around senior managers, then you will have a situation in which a handful of senior leaders are merely responding to external financial pressures and performance indicators. More often than not, the department in such a scenario will come up with service provisions oriented towards those high-level outcomes rather than being open to innovative solutions that might transform the lives of their service users.

The problem is not uncommon. Businesses can suffer from it too. Even the healthcare giant Boots once had to move its innovation unit away from all the corporate pressures of its Nottingham headquarters in order to develop new products.

The lesson seems to be that if you want to seed innovation, you should devolve project leadership. This was certainly the case of the local authorities in our study which were more successful in distributing leadership responsibilities and developing child-centric practices.

Hence, leadership dynamics and working collaboratively with service users are important components in cultures open to innovation. Likewise, in a sort of virtuous circle, receptivity to innovation lays the trajectory for an effective innovation journey.

2 Co-production with service users

It is vital to hear the voices of the care leavers themselves. Full stop. Unless you involve these young people at the earliest opportunity, hear from them about what is working, and what is not working, you will never know the issues to be addressed and never be able to create an authentic service.

“We have a partnership worker, our voice and influence team, and care leavers also have their own consultation group and council,” said a professional from one of the local authorities in our study. “We took the opportunity to ask young people, meaningfully, ‘what do you want the service to look like?’”

And that seems to me to be the way to go. Young people can tell you what is meaningful and going to work, and help to create a truly co-productive ethos.

They also have another important function: they can act as advocates to keep the innovation going.

That goes for the academic research led by Warwick Business School over the past few years as well. We have employed students that are care experienced in the EXIT (EXploring Innovation in Transition) study, which was set up a few years ago with the goal of improving understanding of how social care transition services could be designed to improve outcomes for care leavers.

Engaged as field workers and data analysts, the study team included researchers drawn from Warwick, Newcastle and Bedfordshire Universities as well as Monash University in Australia.

3 Leadership dynamics

In our study, the two most successful local authorities at sustaining innovative services for care leavers were those who distributed leadership beyond senior management to professionals and managers nearer the front line of service delivery.

Leadership from the top may always be necessary for the crucial delivery of children’s services, but our research found that on its own it is never enough to sustain the innovation that is needed to support care leavers.

Rather, middle level leaders, alongside professional champions representing the frontline workforce, where a lot of the knowledge lies, need to be important actors here.

Ideally, the leadership baton should be passed on to someone in the middle of the organisation who is a ‘hybrid’ manager combining a professional background with a managerial role. Hybrid middle managers from one of our case studies played a crucial role in identifying a significant gap in the local service for care leavers from children’s homes, a gap that then could be addressed.

In short, the more people running with an innovation strategy, the better. That could include locally elected politicians who can fight the corner for a non-statutory service when an initial pilot scheme ends, as was the case with one of the local authorities under our review.

4 Measurement of outcomes

We have all heard the old adage, ‘what gets measured, gets managed’. As a result, local authorities have become adept at developing key performance indicators (KPIs) which, once the boxes have been ticked, can mount a case for more funding. More often than not, these KPIs revolve around moving a care leaver out of a residential home into adequate social housing while securing some sort of employment or further education.

Yet so many of the challenges that care leavers face are far more intangible than that, and thus very difficult to measure. Childhood trauma can lead to mental health issues later on, and, as they transition from care to adulthood, care leavers often struggle with identity and attachment issues.

All the more reason, then, to engage care leavers in co-production right from the outset. It will maintain the focus on meaningful outcomes, which are often about a sense of emotional wellbeing.

It will still be difficult to measure this kind of ‘soft’ psychological outcome, but when you are widening the net of stakeholders then you have more chance of seeing not only A and B but also C as well. For a care leaver, A and B may not be what is really going on in their lives.

5 Adaption and learning to sustain and scale up innovation

Nothing stays the same forever, and it is the same with innovation. In order to survive, innovation has to change its shape according to changing circumstances. It has to adapt, if it is not just to become a ‘hollow innovation’.

And so it was with two of our case studies. As they moved beyond their pilot phases, one of the local authorities was looking at how it could roll out its enhanced service provision to more geographical areas of the city under its jurisdiction.

With the other authority, adaptation of innovation focused upon staffing, and services offered, to ensure its meaningfulness was enhanced for care leavers. Despite financial constraints, staffing was increased, and mental health services nuanced in the face of demands from care leavers for more therapeutic input.

Innovation, then, is a journey, just as the life course of a care leaver is a journey. Social care innovation does not end with implementation. It necessarily has to be sustained and scaled up to support care leavers as they journey through life.

As we have seen, our research has identified five key ingredients that can support this sustainability.

Co-production is particularly important. For innovative services to have the greatest effect on life experiences, any intervention is best co-produced with care leavers themselves.

The National House Project, a social enterprise, is a very good example of this. It supports young people in local authorities in England and Scotland to leave care in a supported way. Up to 10 young people form an annual cohort in a 'local house project' supported by the local authority, with the care leavers co-designing the house, empowering each of them to eventually move into their own home.

However, co-production is just one element. If the innovation journey is to work, all the ingredients should be interacting with each other to produce the right recipe for success.

This Core Insights article is based on an academic paper - How to Sustain Pilot Innovation in Public Services: A Case of Children’s Social Care Innovation - which has come out of the EXIT (EXploring Innovation in Transition) study looking at the transition from care to adulthood.

Further reading:

How do we improve outcomes for care leavers?

Measurement for performance improvement - in search of the golden thread

Three ways nudging can improve health outcomes

Graeme Currie is Professor of Public Management. His research interests include leadership, innovation, and strategic change, with a particular focus on public service organisations in fields such health and social care. He has been Principal Investigator for the EXIT study.

Learn more about encouraging innovation in your organisation on the four-day Executive Education course Entrepreneurship and Innovation at WBS London at The Shard.

For more articles on Healthcare and Wellbeing sign up to Core Insights.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok