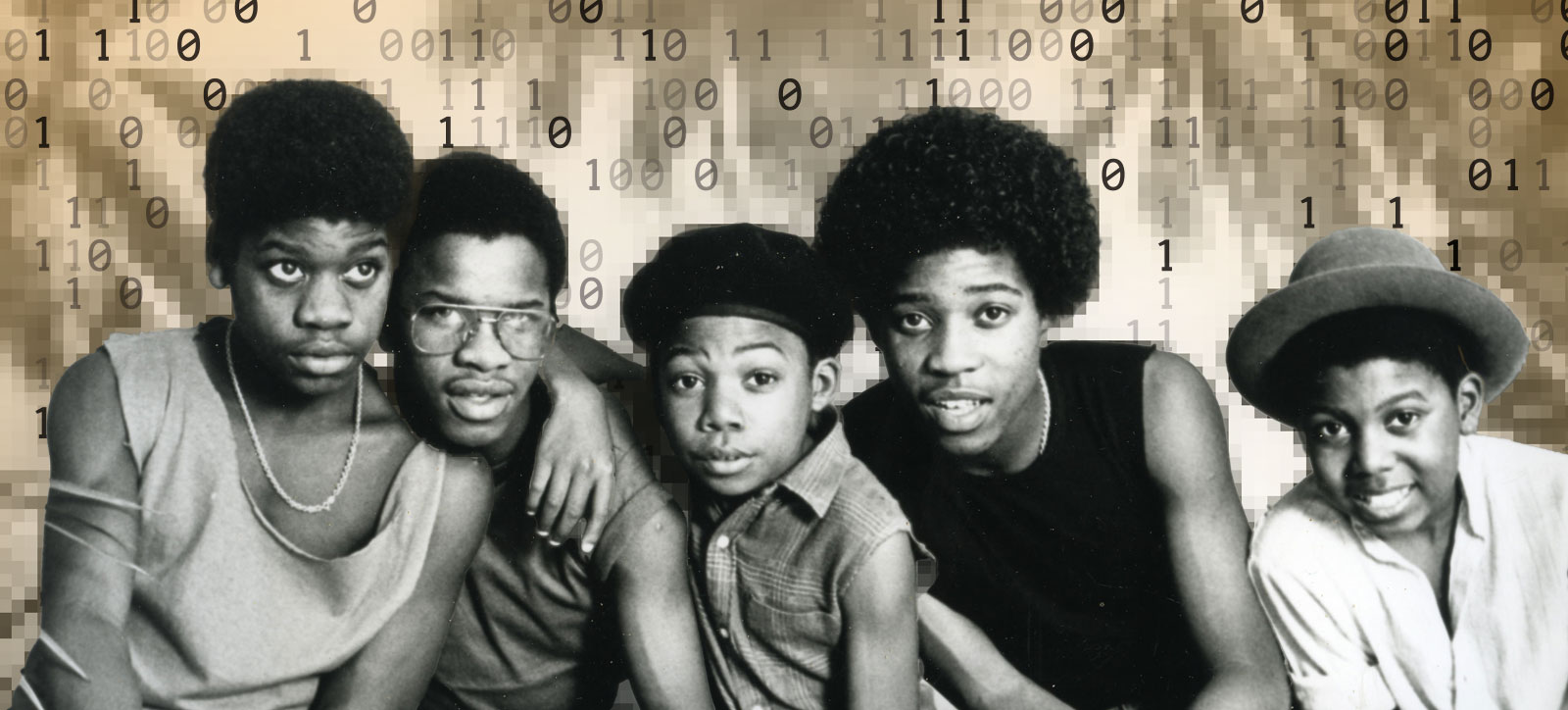

Musical Youth: The hit Pass the Dutchie raised questions about intellectual property in the 1980s just as generative AI is doing today

The story behind Musical Youth’s reggae hit Pass the Dutchie is a curious one.

The song was an unlikely chart topper in six countries including the UK in 1982, selling more than five million copies worldwide, and helping to earn the band a Grammy nomination.

So far, so fairy tale. But there was no happy ending for the five teenagers from Birmingham.

The band were left on the verge of bankruptcy thanks to bad management and powerful industry players who claimed ownership of the song. The profits were distributed via a contract called the Sparta Florida Agreement, which determined the single to be synthetic music – a mix of two previous reggae songs.

Four decades later, much has changed in the music industry and the world in general. Yet the issues at the heart of the of the Pass The Dutchie saga – identity, creativity, and intellectual property – are being revisited in a battle royale between Big Tech and creative industries and artists.

AI: creative ownership vs technological progress

On one side is an artist’s ability to claim legal ownership over their creativity. On the other is the ability of artificial intelligence to learn and develop.

Intellectual property law is already being tested in legal jurisdictions such as the US and the UK, where Big Tech is accused of ‘appropriating’ creative content while developing the original Large Language Models (LLMs).

Legislation is also being formed to determine creative ownership of an artist’s work, most notably in the EU.

The implications will play a big part in determining the future trajectory and location of both the creative and AI industries. They could also leave some actors on the brink of bankruptcy – just like Musical Youth, all those years ago.

So, what are the big issues that the lawyers, practitioners, policymakers, and academics need to consider in this emerging critical debate?

Identity

Questions around identity have long occupied academic minds. Most philosophy students will be familiar with Plutarch’s Ship of Theseus paradox.

This conundrum centres on a wooden sailing ship which, over time, has every piece of its structure replaced, leading to the dilemma of whether the identity of the ‘new’ ship is still the Ship of Theseus or something else entirely.

Thomas Hobbes, a 17th century English philosopher, further elucidated this idea by arguing that if the original planks of the ship were preserved and built into an alternate ship, then which of the two ships would deserve the identity of the Ship of Theseus?

AI is exposing many similar problems, whether it imitates, synthesises or recreates outputs based on pre-existing notions of identity learned from its vast training data.

The Getty Images v Stability AI legal case in the UK is considering a particular feature called the ‘Image to Image’ tool, which allows the user to synthesise a new image from its training data, using text prompts and existing images.

Where, on that continuum of image creation steps, do we determine that the original image or ‘identity’ is materially ‘changed’ and as such, where do corresponding IP claims cease to be relevant?

A leading musicologist determined the Musical Youth version of Pass the Dutchie to be original as he could identify 49 differences from the previous songs, though the band still lost their case for royalties.

So how many differences should determine where the identity of the original artwork, and the copyright covering it, have been infringed – 49 or 490?

One potential solution to protect IP from alleged generative AI exploitation is the adoption of transparency codes of disclosure, or provenance, regarding the use of source materials by the LLMs.

This measure brings challenges, as its approach is somewhat binary: stating that a work was used but not necessarily defining how, leaves us unsure to what degree the source work was used in the creation of the synthetic AI output.

Also, what objective determination could we make about identity even if we did know the exact elements that the AI had used from a protected work? Is it 49 differences or 490 differences that will determine where a copyright is infringed?

At the Gillmore Centre for Financial Technology we consider ‘identity’ to be the next big question and frontier in the development of generative AI. Among others, Professor Ram Gopal, Director of the Gillmore Centre for Financial Technology, is working on this problem.

Creativity

At the heart of the problem is the way that LLMs are trained through the ‘consumption’ of incredibly large data sets. For example, it is estimated that Open AI’s GPT4 was trained on 45 gigabytes of data with 1 trillion parameters.

There is no specific count of documents and even less transparency about the mix of ‘publicly available’ versus ‘licensed’ documents (although LLMs do acknowledge their legitimate use).

This creates a problem in attributing outputs to inputs, referred to as ‘explainability’. The lack of transparency poses a challenge in determining where IP is potentially used but not cited in outputs and for any IP owner, it is practically impossible to police generative AI outputs.

Over the last few months, different IP owners such as media companies the Financial Times, Guardian Media Group, The New York Times and Axel Springer, which ownsGerman daily Bild and website Politico among others, have concluded content sharing agreements with the Big Tech owners of the leading LLMs.

Reports suggest that many of these agreements still rely on trust and good faith to explain the link between creative content and synthetic outputs. There are a number of legal cases and forthcoming legislative initiatives that will try to tackle this problem, but these are likely to be protracted and even contradictory, spanning multiple jurisdictions and legal codes.

In this context the technical alternative might be the development of Small Language Models (SLMs), which have the benefit of greater explainability, transparency, affordability and accessibility.

The Gilmore Centre has been developing an SLM called GilmoreAI which uses only peer-reviewed academic papers and conference speeches as the data for its training model, in order to output topics on narrow fintech related questions. This ensures not only the quality of the output, but also the veracity and legality of the inputs used to train the model.

Although there is an arms race among Big Tech in the development of LLMs there are many reasons to believe that SLMs will develop rapidly in parallel.

Intellectual Property

In the coming months, there will be some important considerations for the likes of Google and Microsoft and downstream businesses regarding IP and generative AI.

First, in the US the issue of ‘fair use’ will be tested in the California and New York courts. The case of Silverman et al argues that the similarity of generative AI outputs to an author’s original work is of less importance than that the work has allegedly been used undeclared to infringe copyright. The alleged claim in this particular case is that LLMs used pirated versions of the author's works from the internet.

A novel test of this principle might be to ask an LLM to compose text in the style of JD Sallinger, author of 1951 classic The Catcher in the Rye. Creation of a convincing output would evidence that, at some point in its training, it had consumed Sallinger’s very limited works, as he was notoriously reclusive and gave little in the way of media interviews. We might term this the ‘Sallinger test’ for AI.

However, it remains to be seen how the US courts will determine whether this is ‘fair use’ given the availability of his pirated work on the internet. Would use of pirated works form a misdemeanour? And would this test fail if the creators of LLMs had already made an agreement with the Sallinger estate?

Second, in the UK Getty Images v Stability AI case, the location of data use will become very important vis-a-vis English copyright law. For English law to be invoked, the data and development teams tasked with building an LLM will need to be located in the UK at some point and issues surrounding cloud computing infrastructure are likely to be material.

The UK Getty Images case will also examine whether an AI model contains an infringing copy of its own training data. This may open up greater transparency around the architecture of some of the major LLMs, which so far has been obscured.

Finally, policy is beginning to determine frameworks for the governance of IP and AI. The UK Patent Office is currently consulting on the issue, but recommendations are unlikely to emerge until at least 2025 with legislation still unconfirmed.

How EU regulation could shape the future of generative AI

The EU has made more rapid progress and is already deploying a legislative framework on AI that will be adopted in stages between 2024 and 2026. However, businesses are already being encouraged to deploy the requirements and principles of the act ahead of time.

This EU act will be a world first and will build on the transparency and risk principles established under the EU's GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) in 2018. It seems likely that it will require explicit consent from all copyright holders before protected works can be used for training AI, regardless where that training takes place. Responsibility for compliance is likely to fall on both the providers and the deployers of AI technology.

This provision will override the considerations of fair use in US copyright law and jurisdiction in English law, making the EU law effectively borderless for both providers and deployers of LLM systems.

Although business has no choice but to adopt generative AI for its limitless benefits, the risks inherent in those systems should be carefully considered as law solidifies in this area. The Gillmore Centre will be exploring many of these policy implications at its Digital Currencies & AI Policy Forum at WBS London at The Shard in November.

Despite the hype and overstatement, there is no doubt that generative AI will re-shape business and many other areas of our lives.

The race to regulate AI and intellectual property

Right now, we are at an inflection point in generative AI's rate of growth. If the critical resources for its establishment and development turn out to have been acquired without due regard to IP rights, and if those rights are enforced legally across jurisdictions, then there will be significant consequences for Big Tech and businesses who deploy the technologies.

The battle will play out in courts and legislatures, which will leave many businesses averse to regulatory risks - especially in the financial services sector.

Greater internal compliance and governance of AI deployment will most likely increase. These policy debates may also herald the adoption of a rise in SLMs with narrower uses and defined, often proprietary, learning data provenance.

A strong claim remains that generative AI ‘creations’ are synthetic, just like those produced by humans whose creativity is influenced and inspired by those who came before them.

Even so, we might expect changes to Big Tech business models, where IP rights use in training data is acknowledged through financial settlements en masse. In that case, the deal struck with the likes of the Financial Times is likely to be just the first of many.

Over time generative AI will move further away from these human-derived origins as creativity becomes based on synthetic antecedents. We can already see that happening on music platforms like Spotify, where AI-created music has already formed its own category, far-removed from its human-inspired and trained origins.

Thinking back to Pass The Dutchie, many would argue that reggae (like all music), was always iterative and derivative. Should we expect generative AI to be different to how humans use ‘influences’ to become ‘creative’?

If that becomes the settled case in the era of generative AI, we might see a change in creativity and taste inspired by machines.

And Musical Youth might finally receive the full royalties from their song.

Further reading:

Who will benefit from AI in the workplace - and who will lose out?

Do the rewards of AI outweigh the risks

Beyond the hype: What managers need to know before adopting AI tools

Matt Hanmer is an Honorary Research Fellow at the Gillmore Centre for Financial Technology at Warwick Business School.

The Gillmore Centre for Financial Technology was launched in 2019 to conduct world class research on fintech and AI. It was established thanks to a £3 million donation by Clive Gillmore, founder and Group CEO of Mondrian Investment Partners and an alumnus of the University of Warwick.

It conducts

Learn more about AI and digital innovation on the four-day Executive Education course Business Impacts of Artificial Intelligence at WBS London at The Shard.

For more articles on Digital Innovation and Entrepreneurship sign up to Core Insights.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok