In this fifth lesson of a six-part series, I explain the importance of holding each other to account for behaviours to foster an improvement culture.

Publishing one lesson a month, my goal is to share lessons from my evaluation of the five-year long NHS partnership with the US Virginia Mason Institute, and foster a global conversation about how to lead improvement within healthcare organisations and systems.

Each lesson is followed by a ‘tweetchat’ on Twitter hosted by WBS in partnership with the #QIhour network. The lessons are summarised in Six key lessons from the NHS and Virginia Mason Institute partnership. You can join in the conversation at 7pm (BST) on Tuesday 6 June via Twitter using the hashtag #LeadingQI.

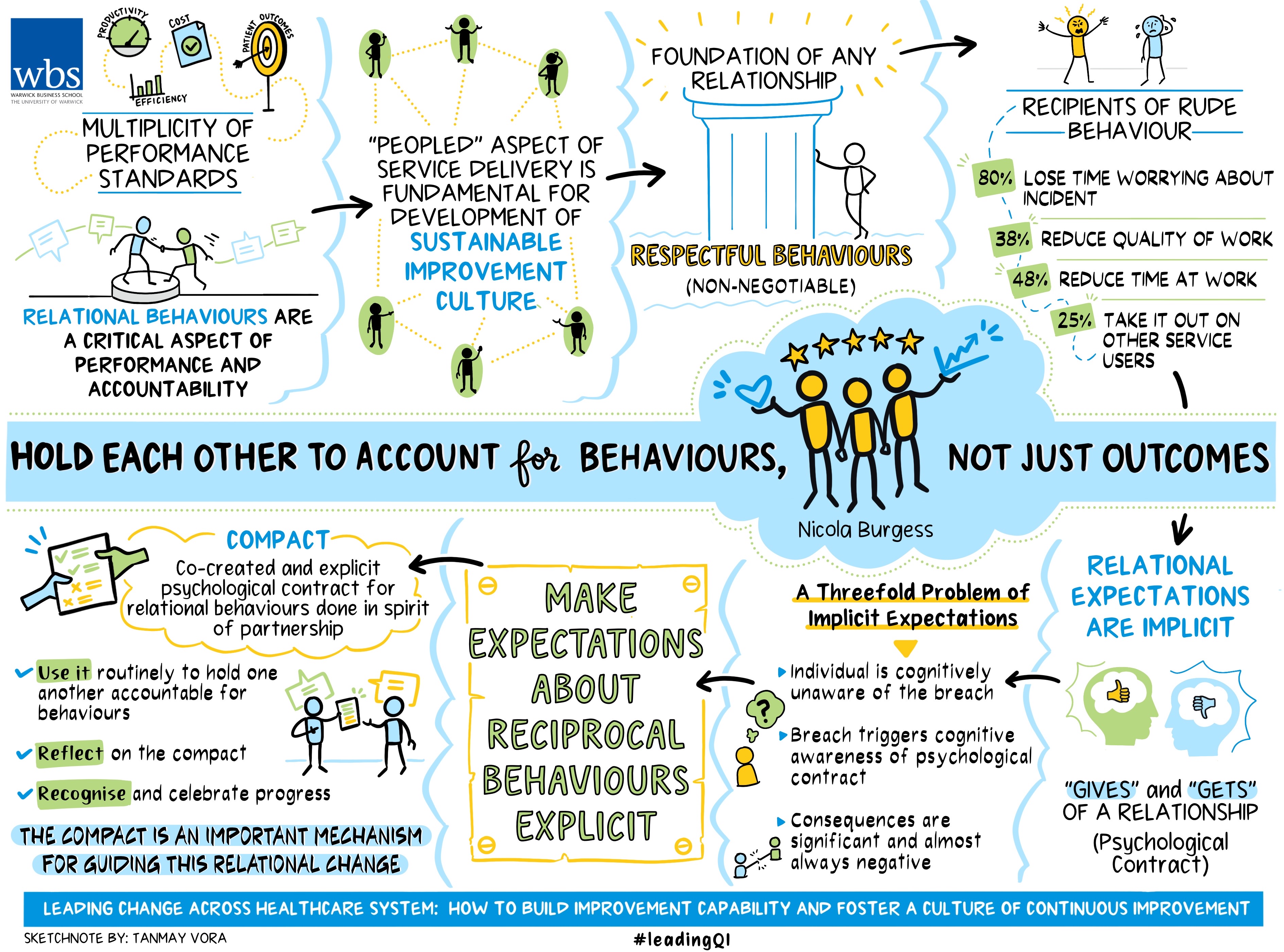

National Health Service organisations are expected to deliver against a multiplicity of performance standards relating to productivity, efficiency, cost and patient outcomes.

The most well-known standards in the English NHS include a four-hour waiting time target for Accident and Emergency, as well as targets around cancer referrals, infection standards, and length of stay.

That standards have an important role to play in the delivery of high quality, affordable and equitable care is not in dispute, but of course, they are not without problems either. I will explore the paradox of measurement in more detail in lesson six. Here, I want to focus on another aspect of performance and accountability, that of relational behaviours.

Why relational behaviours are important

The ‘peopled’ aspect of service delivery is fundamental for development of a sustainable improvement culture. In lesson one, we talked about the importance of setting an organisation’s values in ways that align with the values of the people who work there. Lesson 2 proposed an improvement infrastructure that instills a set of routines and practices to foster connections across hierarchical levels, while lessons three and four explained the importance of senior and middle level leaders connecting with others for improvement and innovation.

So, having established that relationships are important, how might we hold each other to account for relational behaviours?

Some behaviours are non-negotiable

Adopting respectful behaviours is a foundational aspect of any relationship. Yet conflicting priorities, mounting pressures and constrained resources can lead even the saintliest individual to experience stress-induced fury.

For others, negatively charged interactions are the norm. Not only is this unacceptable, it is also significantly damaging to productivity and can even be dangerous.

Respectful behaviours are frequently overlooked for their ability to elevate performance and improvement or (in their notable absence), significantly undermine it. Research by Professors’ Christine Porath and Christine Pearson found 80 per cent of the recipients of rude behaviour lose time worrying about the incident, 38 per cent reduce their quality of work, 48 per cent reduce their time at work and 25 per cent take it out on other service users!

Readers working in a healthcare context may be familiar with this research and the work of the #civilitysaves social movement. #Civilitysaves came to my attention when I listened to an engaging presentation from an emergency medicine consultant with the message ‘Arseh*les kill people’.

Individuals hold implicit expectations about the ‘gives and gets’

Most employment relationships are subject to an explicit contract of employment (a legally binding document that sets out the terms and conditions of employment), and an implicit ‘psychological contract’, which refers to an individual’s perceptions about the ‘gives and gets’ of the relationship.

For example, an employee might expect to receive time-off in-lieu having repeatedly worked in excess of their contracted hours to complete work ahead of a deadline. If this fails to align with the expectations that make up an individual’s psychological contract, a ‘breach’ is incurred. For the individual, a breach is experienced cognitively as a negative emotional response.

The problem here is three-fold. First, since the psychological contract is implicit, the individual is cognitively unaware of it until they experience a breach. Second, the breach ‘triggers’ cognitive awareness of one’s psychological contract, and an emotional response rapidly ensues. Third, the consequences of a breach are significant and almost always negative.

For example, employees may experience a decline in wellbeing and morale, a reduction in work effort and productivity, and may eventually (or perhaps dramatically) exit the organisation. In sum, when the psychological contract is implicit, a breach can be hard to spot, hard to avoid, and subsequently hard to repair.

Given the significant impact of a breach to the psychological contract, organisations should seek to make expectations about reciprocal behaviours (the ‘gives and gets’), explicit.

This can be done with a ‘compact’, an explicit (written) psychological contract that can become an effective mechanism for holding ourselves and others to account for behaviours.

A Harvard Business School case study of a Virginia Mason Medical Centre described how a severe financial crisis at the hospital led CEO Gary Kaplan to confront doctor’s long-held (implicit) perceptions of ‘entitlement, autonomy, and protection’ that ran counter to the survival of the organisation.

The subsequent introduction and co-creation of a ‘compact’ represented a ‘new deal’ between the leadership team and hospital doctors that became both a catalyst for change and a mechanism for holding doctors and hospital leaders to account for behaviours.

In the following video, Mr Kaplan explains how and why he implemented the compact at Virginia Mason and how it is still in use today.

The NHS-VMI partnership - how a compact fostered relational change

Unique to the NHS-VMI partnership was a monthly six-hour meeting between all five hospital CEOs and senior representatives of NHS Improvement and NHS England (NHSE).

This meeting, known as the Transformation Guiding Board (TGB), was underpinned by a compact co-created by the five CEOs and members of NHSE (see this blog published by NHS Providers for a detailed description of the NHS-VMI compact).

Pledging allegiance to a ‘spirit of partnership’, the TGB elected to prioritise more relational forms of accountability and governance to foster inter-organisational learning and collaboration.

Remarkably for the NHS, they agreed that no performance standards would be aligned to the partnership; instead they expected to see improvements in quality, safety, morale and finance. In sum, the compact represented ‘a new deal’ between a service provider and their regulator. An abridged version of the NHS-VMI compact is shared below.

Researchers at WBS conducted monthly observations of the TGB for two years. We found the meeting fostered a ‘safe space’ for CEOs to share experiences with implementing improvement routines and methods in their organisations, and the challenges they faced, without fear of reprisal from those whose job is to regulate (see our paper in BMJ Quality and Safety for more detail). Over time, we started to see how the compact became a mechanism for partnership members to hold themselves and one another to account for behaviours, not outcomes.

Understanding how and why the compact works is important

To be effective, a compact needs to be more than a document created at the start of a relationship and never to be referenced again.

It must be more than a poster on a wall or sellotaped to the back of the toilet door (although this is the better option of the two). The power of a compact can only be realised if it is routinely used to hold one another to account for behaviours, remembering that these behaviours are the ones that enable the partners to work towards a shared goal.

To this end, the compact was a standing agenda item concluding each monthly meeting. ‘Reflections on the compact’ was an opportunity for everyone to verbally reflect what they had learned from the meeting.

This ritual reflection triggered cognitive attention to the behaviours set out in the compact. Since reflections identified mutual learning and respect for one another, the reflective process evoked a positive emotional response. Ergo, by making the psychological contract explicit, we can more readily and frequently recognise and celebrate progress in ways that help us maintain partnership ways of working.

As with all relationships, behaviours don’t always align to promises made. Again, the monthly meeting provided a ‘safe space’ for members to ‘call out’ when things went wrong and work together to make sense of the problem and engage in collective problem-solving. In other words, making the breach visible to all partners provided an opportunity to repair the transgression and helped members continue to work towards their shared goal.

The relationship between the five CEOs and the regulators was successful overall and paved the way for new collaborative ways of working. The compact was an important mechanism for guiding this relational change.

However, context also plays a role in shaping new relational behaviours. For example, the TGB benefited from an exclusive membership of senior representatives of each organisation and each member committed to focus discussion on the partnership for a full day, without distraction.

This exclusive membership was conducive to the creation of trusting behaviours, enabling conversations that were honest, reflective, supportive, and valuable. The chief executives regularly told us it was “the best day of the month!”

However, these relational behaviours were less visible outside the monthly meeting.

At least part of the explanation for this lies in a lack of ‘socialisation’ of the compact with others outside the scheduled meeting and beyond the TGB’s membership.

This raises the question as to whether a compact might best be restricted to smaller groups of people or organisations seeking to work in new relational ways (such as the TGB described here), or whether the compact can (and should) be spread across larger groups of people within the same or different organisations.

What we do understand through our research is that a formal routine (such as a monthly meeting), can be utilised as a trigger to activate conscious attention to the enactment (or otherwise) of the desired relational behaviours made explicit by the compact.

The tweetchat on the importance of social networks in continuous improvement will be held on Tuesday 6 June at 7pm BST via Twitter using the hashtag #LeadingQI.

Nicola Burgess is Reader of Operations Management and teaches Operational Management on the Distance Learning MBA plus Digital Innovation in the Healthcare Industry on the Executive MBA.

More lessons from the Virginia Mason Institute – NHS Partnership:

1 Build cultural readiness as the foundation for better QI outcomes

2 Embed QI routines and practices into everyday practice

3 Leaders show the way and light the path for others

4 Relationships aren’t a priority, they’re a prerequisite

5 Hold each other to account for behaviours, not just outcomes

6 The rule of the golden thread: not all improvement matters in the same way

Follow Nicola Burgess on Twitter @DrNicolaBurgess.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok