Old King Coal: The last UK coal-fired power station has closed but the UK relies on gas imports

The recent closure of the UK’s last coal-fired power station was a significant milestone.

Ratcliffe-on-Soar ceased operations on September 30 – 142 years after the world’s first coal-fired power station at Holborn Viaduct in London began generating in 1882.

With coal gone, the next target of climate policy is to phase out natural gas.

But if coal suffered a ‘long death’, dragged out over half a century, we have a far smaller window to transition away from natural gas.

For now, the UK energy system is highly gas dependent, and gas security remains an urgent concern.

The prospective phasing out of the UK’s enormous gas infrastructure also raises huge financial and co-ordination challenges.

UK dependence on gas imports

Cheap North Sea gas in the 1990s led to Britain’s so-called ‘dash for gas’. By the end of the decade, gas was responsible for 43 per cent of total UK inland energy consumption.

First gas, then renewables, pushed coal out of the electricity system.

But this glut was short-lived. Gas production on the North Sea halved between 2005 and 2011. Today, we depend on imports to meet 46 per cent of gas consumption.

In 2023, Norway accounted for 58 per cent of all UK gas imports. The remaining 42 per cent arrived on tankers as Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG).

Of those cargoes, 61 per cent arrived from the United States and 14 per cent from Qatar.

While the UK has two gas pipeline ‘interconnectors’ with Europe, these were being used to export, rather than import, gas.

The UK energy system remains profoundly reliant on gas, which accounts for 36.6 per cent of all inland energy consumption. Gas accounts for more than a third of all electricity generation and provides flexible supply to the grid that is difficult to replace.

As we know, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 precipitated an ongoing European gas price crisis.

In its recent State of the Energy Union report, the EU calculated that Russian gas (pipeline and LNG) fell from 45 per cent of all imports in 2021 to 18 per cent in the first half of 2024.

This is not because the EU has sanctioned Russian gas – it hasn’t. Instead, Putin has throttled pipeline flows into Europe, destroying the state-controlled Gazprom’s most lucrative export market in the process.

The UK was never a major recipient of Russian gas, but it is exposed to the impact of Russia’s actions on the European and global gas markets.

The cost of the gas price crisis

To cover the shortfall in Russian supplies, Europe pivoted to the global LNG market. This led to a price war, driving a monumental spike in spot LNG gas prices in 2022.

In the UK, the result was a cost-of-living crisis exacerbated by two features of the country’s energy system. First, four in every five households in the UK rely on gas for heating, directly exposing them to increased gas prices.

Second, households are indirectly exposed to gas prices through the electricity system. This is because in the UK, electricity prices are currently set by the price of gas-fired generation.

While Europe has experienced a severe price crisis, forcing governments to pay out hundreds of billions to protect consumers, it has managed to get through the last two winters without a physical shortage of gas and major blackouts.

This is down to effective policy, and a large dose of luck – two mild winters, and muted demand in China, proved crucial.

The gas price crisis is far from over. Ofgem’s price cap sets household energy prices – per unit of energy – for those on default tariffs.

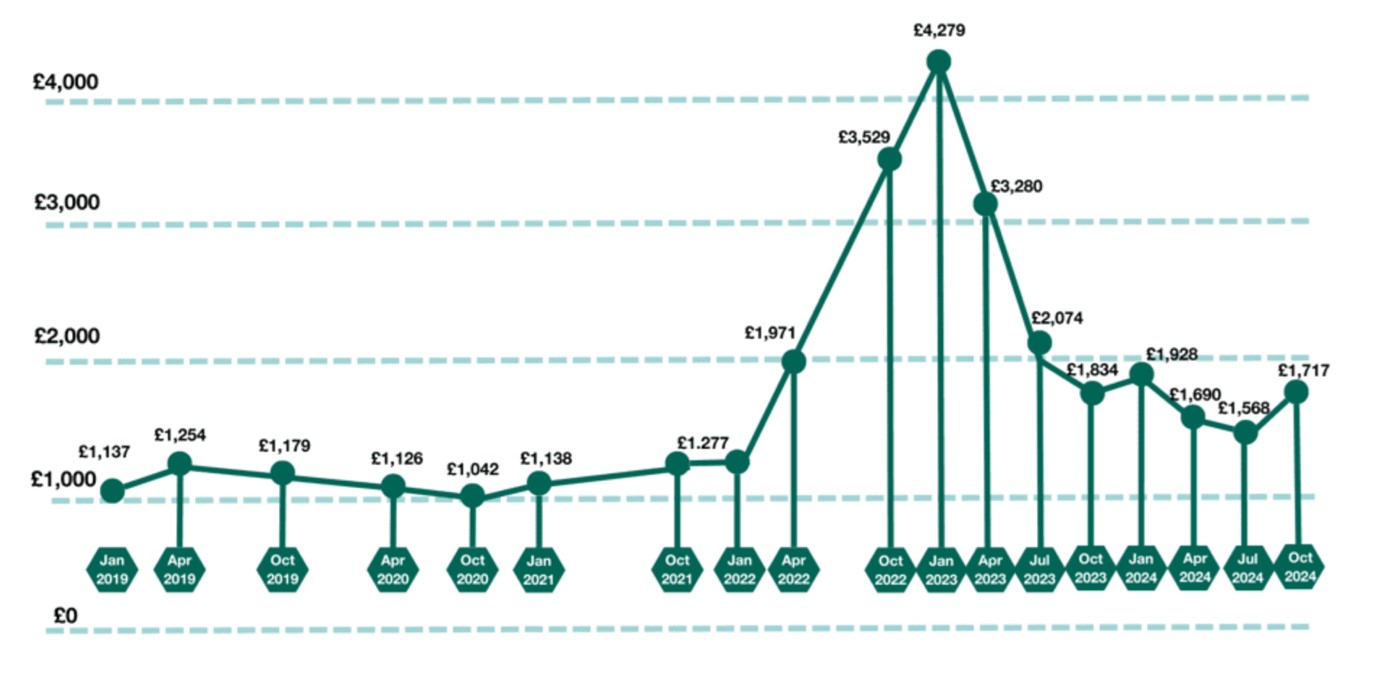

The figures in the graph below are given for a typical household using gas and electricity and paying by direct debit.

The current cap is well below the peak in January 2023 - though the UK Government’s Energy Price Guarantee protected consumers from the brunt of that. However, it remains 48 per cent above the average between January 2019 and January 2022.

It is widely expected that the cap will increase again in January 2025, likely moving towards January 2024 levels.

What’s driving this increase? Recently, a warm summer in Asia pulled spot LNG cargoes to the continent’s shores.

Geopolitical uncertainties, especially the escalating traumas of the Middle East, mean that traders are jittery about the prospects of what many expect to be a cold winter in the northern hemisphere. The current European gas price is at a 10-month high.

But the underlying, structural problem is the continued imbalance of the global LNG market.

Why the gas crisis will last one more winter

When the gas crisis struck in the Spring of 2022, those in the LNG industry talked of it being at least a ‘three winter crisis’. LNG production is not as flexible as oil, is highly cyclical, and LNG plants tend to run at maximum capacity.

It takes around five years to build a new LNG terminal once a final investment decision has been made and shovels are in the ground – giving us a timeline of future capacity over the short-term.

The gas crisis struck when markets were already tight, and little new capacity was expected over the next few years.

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) latest Global Gas Security Review, global LNG production is forecast to grow by two per cent - 10 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2024. That is the slowest growth rate since 2020.

At the same time, global LNG demand growth is expected to be over two per cent, meaning that demand growth will outstrip supply growth.

Exacerbating matters, the gas transit agreement between Russia and Ukraine expires at the end of the year with no prospect of renewal. This will reduce the remaining supply of Russian gas to southeast Europe by around 15 bcm. A cold winter, and Europe will be competing in a fierce global LNG market for additional supplies.

This prognosis is reflected in the recently-released Gas Winter Outlook 2024 from National Gas, the UK’s gas infrastructure body.

The problem is not UK gas demand or infrastructure. System demand is expected to fall year-on-year because the UK is exporting less gas via its two interconnectors with Europe, which enjoys high storage levels and new LNG import infrastructure of its own.

National Gas judge that, even if the UK were to experience a one-in-20 peak in winter demand and lose its single biggest piece of gas infrastructure, the country would still enjoy an excess supply margin of 55 million cubic metres.

The risk is the finely balanced global LNG market, which means that any “unexpected weather, geopolitics or supply disruption” could leave the UK paying premium prices to attract spot LNG cargoes.

Beyond this winter, however, the global LNG market should begin to rebalance. A wave of new LNG production capacity is expected in the next few years, starting in 2025.

Expansion in the US and Qatar is well underway and new production is also coming online elsewhere, like in Mexico and Canada.

There is some uncertainty about timing. The current pause in some US projects is causing delays, and projects often take longer than anticipated.

Nonetheless, the IEA predicts that LNG supply will grow by nearly six per cent (or 30 bcm) in 2025 and that the US will account for about 85 per cent of that growth.

When Qatari expansion is included alongside a host of other new projects underway, the IEA estimates that more than 270 bcm per year of additional export capacity could be added by 2030.

The IEA concludes that this should “loosen market fundamentals and ease supply security concerns in the second half of the decade”.

Phasing out gas

With coal gone, gas is now the most carbon-intensive element of the UK’s energy mix.

To stay within the country’s legally binding carbon budget, gas demand has to go the way of coal, but more quickly. Growing dependence on LNG imports, even if the market in the second half of this decade is rebalancing, entails continuing price volatility risks.

Domestic heat is by far the greatest challenge. The last UK Government deferred making a final decision on the preferred technology mix for domestic heating until 2026.

It is widely expected that the Government will favour electrification, accelerating falling gas demand. But, in a step in the opposite direction, the Government recently announced a £22 billion support package for carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects.

This will support the production of blue hydrogen to decarbonise industry using natural gas as a feedstock with CCS, as well as the use of CCS on new gas-fired power stations to provide lower carbon flexibility.

If successful, this will keep some demand for gas in the mix for longer, and while CCS aims to capture the majority of emissions at the point of combustion, it will do nothing to reduce upstream emissions.

Independent think tank Carbon Tracker estimates that the upstream emissions of US LNG, on which the UK is set to become increasingly dependent, are three to five times that of Norwegian pipeline gas.

Three paths to net zero in the UK

There remains huge uncertainty over the pace at which the UK can and will phase out natural gas.

The National Energy System Operator’s recent Future Energy Scenarios give us one range of possible outcomes.

They present three net zero pathways – holistic transition, electric engagement and hydrogen evolution – alongside a counterfactual scenario that does not meet the UK’s climate targets.

Put simply, the higher the level of electrification and the lower the reliance on blue hydrogen, the faster the fall in gas demand.

In all cases import dependency increases, with gas imports accounting for a greater share of UK gas consumption. But the absolute volume of gas imports required differ markedly.

In their estimation, baseline UK gas demand in 2023 was 79 bcm, and import dependency was 57 per cent.

How do their scenarios for the future compare? In their holistic transition pathway absolute gas demand in 2035 would be 39 bcm – 50.6 per cent lower – and import dependency would be 71 per cent.

By comparison, in the hydrogen evolution pathway gas demand in 2035 would be 50 bcm – 36.7 per cent lower – and import dependence would be 77 per cent.

Finally, under the counterfactual, which misses net zero, demand in 2035 could be 61 bcm – 22.8 per cent lower – and import dependence would be 81 per cent.

All this suggests that accelerating the low carbon energy transition is essential to reducing the UK’s reliance on global gas markets. But that won’t be straightforward.

Policymakers, think tanks and academics are only just starting to grapple with the complexities of phasing out natural gas in the UK.

The decline of coal was not well managed and came at a tremendous cost to those communities involved in its production and the industries that relied on it.

Already, the UK Government’s decision not to allow new exploration licenses for oil and gas in the North Sea is raising parallel concerns.

Decommissioning the gas distribution network

Yet, when it comes to end-use consumers, there is a key difference between phasing out coal and gas.

The final demise of coal went unnoticed by electricity consumers. This is because, as the UK power supply decarbonises, the energy services provided to consumers will remain basically the same.

Natural gas, by contrast, requires a dedicated infrastructure to supply consumers. Decarbonisation, in this case, means retiring a vast, tentacular national infrastructure reaching into most of the country’s homes.

The UK’s National Transmission System comprises 7,600km of high-pressure pipelines, and the low-pressure Gas Distribution Network stretches across 276,000km of pipelines.

This is arguably the UK’s single most significant piece of critical infrastructure. As gas demand falls – and it fell a further 10 per cent in 2023 – there will be fewer and fewer customers on the network to cover its costs.

Questions remain unanswered about how this decline will be managed. Will bills be brought forward to compensate for falling customer numbers in the future?

How will decline be co-ordinated across geographies, in sync with net zero targets, and to protect vulnerable customers?

A recent UK Government-commissioned analysis suggested that the cost of decommissioning the network could be as high as £70 billion. Who is going to pay for any of this?

In the face of the gas price crisis, the Labour Government has understandably placed emphasis on the reduction of gas demand via the greening of the power system.

One of its headline ‘missions’ is to achieve a green power system by 2030. But it is imperative that the Government complements its strategy for the growth of green power, with a strategy for the decline of the gas system.

Failure to do so could result in the end of gas proving as challenging as the end of coal.

This Core Insights article is based on a briefing paper for the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC).

Further reading:

How can the world reach net zero?

Cutting demand for gas: The key to preventing UK energy crisis

A new strategy for the UK Government to meet heat pump targets

Why firms need to start measuring Scope 3 emissions now

Michael Bradshaw is Professor of Global Energy and is a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and the UK Energy Research Centre. He teaches Managing Sustainable Energy Transitions and Managing Sustainable Energy Transitions (Outside the UK) on the Full-time MBA and Executive MBA.

Louis Fletcher was a Research Fellow at Warwick Business School before joining the Politics and International Studies department at the University of Warwick. He also works with the UK Energy Research Centre.

Learn more about making your organisation withstand a rapidly-changing environment on the four-day Executive Education course Leading an Agile and Resilient Organisation.

Discover more about Sustainability and the energy transition with our free Core Insights Newsletter.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok