How strong relationships are across a hospital is vital for new improvements to work

In this fourth lesson of a six-part series, we discuss how relationships, networks, and connectedness among professionals matter for continuous improvement. This lesson focuses on sharing key insights from the evaluation of the NHS partnership with the US Virginia Mason Institute. By sharing a lesson each month, we aim to foster a global conversation about how to lead and sustain improvement within healthcare organisations.

Each lesson will be followed by a ‘tweetchat’ on Twitter hosted by WBS in partnership with the #QIhour network. You can join the tweetchat on April 25 at 7pm (BST) using the hashtag #LeadingQI. The lessons are summarised in Six key lessons from the NHS and Virginia Mason Institute partnership and the published evaluation report can be found here.

Research has shown social networks represent a significant factor in an organisation’s success or failure. Social networks embody the relational infrastructure through which knowledge (including tacit knowledge) can be mobilised to facilitate collaboration for improvement.

For a sustainable culture of continuous improvement to embed within organisations, people must be able to share knowledge, collaborate for improvement, make sense of changes and adjust accordingly.

Put simply, it is through relationships that people enact change, and these efforts will fail if organisational leaders neglect to support them.

Social networks under the microscope

An organisation’s social network emerges from the day-to-day interactions of professionals and are the basis of ‘how we do things’. These formal and informal relationships act as channels to support the co-ordination of information, knowledge, and resources among individuals and teams.

Through planning and testing of ideas, conversations among organisational staff foster shared understandings that govern whether a new way of working is accepted. Organisational social network analysis (OSNA) is a systematic approach to uncovering and visualising the presence and patterns of relationships, and the flow of information, influence, and collaboration within and across organisational settings.

We used OSNA to understand how knowledge about improvement was being mobilised among healthcare professionals within each of the five hospitals that took part in the five-year partnership between the NHS and the US-based Virginia Mason Institute (VMI).

The results provided a striking illustration of the relationship between the social connectedness of an organisation’s participants and its capacity for collaboration, innovation, and improvement. Specifically, we found network density (the number of connections present within the network), and the reciprocity of relationships between healthcare professionals, accounted for differences in both the efficacy of the improvement programme and organisational performance.

Magnifying relationships: how knowledge is shared

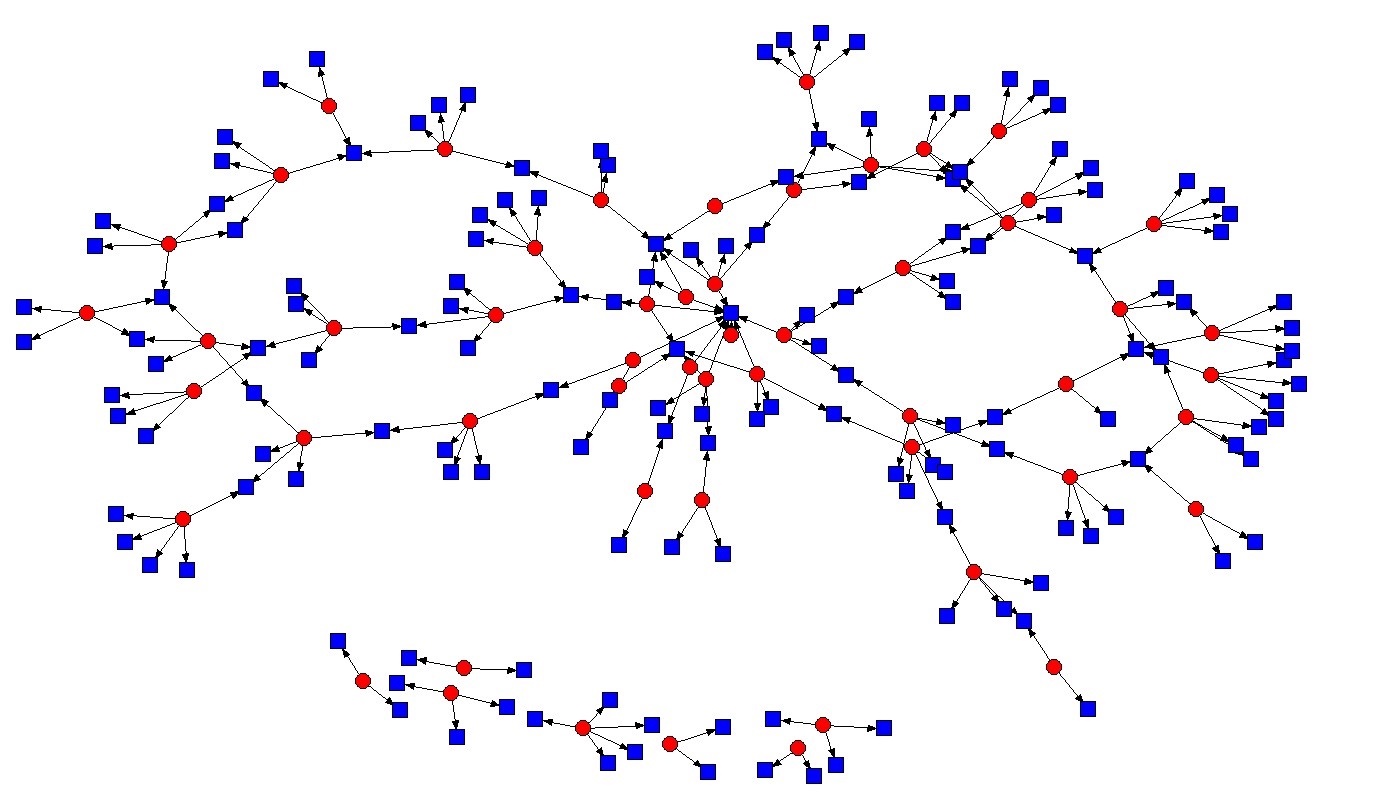

The graphs below contrast the social network of a high performing organisation (Figure a) with a low performing organisation (Figure b).

Figure A: The social network of a high performing organisation

Figure A: The social network of a high performing organisation

Recall in lesson two that both organisations had received extensive support to implement an identical improvement infrastructure: they each had access to the same training programme, delivered to the same high standard, supported by highly skilled improvement facilitators and identical leadership routines. Yet the level of engagement and degree of traction among healthcare leaders in these two organisations was significantly different.

In both graphs the red circles represent professionals with improvement skills and knowledge and the blue squares depict staff with whom knowledge related to improvement was being sought and shared.

Figure A revealed the high performing organisation embodied a densely connected network with a high capacity to facilitate knowledge exchange and collaboration for innovation and improvement.

Respondents at this organisation often said: “Everybody’s talking about improvement.”

Figure B: The social network of a low performing organisation

Figure B: The social network of a low performing organisation

Conversely figure B depicts an organisation where there were sparse, non-reciprocal interactions among isolated professionals, representing a low capacity to facilitate collaboration and knowledge exchange. It is notable that this organisation had recently moved into ‘special measures’, and an independent report had found evidence of a bullying culture among members of the senior leadership team.

Who’s talking to whom?

The network diagrams produced by the team at Warwick Business School have been shared widely by practitioners and healthcare leaders. The popularity of these diagrams ostensibly lies in making visible the relational ties that permit knowledge exchange for meaningful collaboration and improvement.

But there is more to these network diagrams than meets the eye.

Specifically, our data reveals it’s ‘who is talking to whom’ that matters. Below we compare the relational characteristics of three of the NHS-VMI partner hospitals to explain why ‘who is talking to whom’ matters for improvement.

Analysis of figure A reveals knowledge about improvement in this organisation was predominately mobilised by practitioners. Specifically, this network displayed a high degree of interaction and engagement among its clinical professionals.

The characteristics of this type of network were ideal to mobilise knowledge for meaningful collaboration and improvement.

Figure C: This organisation's circular characteristic denotes highly efficient communication channels

Figure C: This organisation's circular characteristic denotes highly efficient communication channels

Meanwhile, our analysis of figure C reveals a neutral knowledge sharing environment, where no group dominated another, and each group mutually interacted to collaborate and share improvement knowledge.

The distinctive circular characteristic of this network suggests knowledge was mobilised with efficiency and without creating a bias around the value of improvement and training.

Notably, this organisation employed more than 18,000 staff, hence highly efficient communication channels are of key importance.

Figure D: This organisation's social network saw senior leaders dominate

Figure D: This organisation's social network saw senior leaders dominate

In figure D we observed a high degree of connectivity among senior leaders and the improvement teams, but these relationships were found to dominate the network.

Relationships overall were non-reciprocal and collaboration among practitioners was limited.

This organisation made significant progress initiating improvements within several departments, but a lack of collaboration among practitioners limited progress and made it difficult for improvements to embed.

Relationships are not a priority, they are a pre-requisite

Many have interpreted our network graphs as ‘evidence’ of a link between organisational culture, improvement, and performance. We do not refute this link; we merely reiterate our intention was to establish how knowledge about improvement was mobilised (or not), and to whom.

Ultimately, a key finding of the NHS-VMI evaluation was that highly connected networks with reciprocal, collaborative relationships, achieved greater traction across the organisation in less time, delivering improvement that was more substantial and longer lasting.

Of the five hospital trusts involved in the NHS-VMI partnership, the highest performing organisation embodied relational networks that were ‘dense’, distributed, reciprocal, and thereby capable of gathering support about the value of improvement and the adoption of improvement routines and practices.

Conversely, the poorest performing organisations embodied social networks characterised by non-distributed and non-reciprocal relationships that make improvement knowledge challenging to mobilise, and new behaviours and practices difficult to embed and sustain.

To conclude, relationships send the message of whether improvements will make a beneficial change to practice and determines whether improvement activities embed within an organisation.

Organisations that exhibit high levels of social connectedness have the highest capacity to facilitate knowledge exchange and co-ordinate activity for meaningful collaboration and improvement. Hence organisational leaders should pay attention to supporting relational connectedness that is distributed across hierarchical levels, departments, and teams.

To learn more about how leadership routines supported the high levels of social connectedness represented in figure A, see our blog ‘Can pizza lead to service improvement in the NHS’ published by NHS Providers.

The tweetchat on the importance of social networks in continuous improvement will be held on Tuesday April 25, 7-9pm (BST). Follow the hashtags #LeadingQI and #QIhour to join and learn more from the NHS-VMI Partnership.

Nicola Burgess is Reader of Operations Management and teaches Operational Management on the Distance Learning MBA plus Digital Innovation in the Healthcare Industry on the Executive MBA.

Follow Nicola Burgess on Twitter @DrNicolaBurgess.

Emily Rowe is Assistant Professor at Warwick Medical School after completing her PhD at WBS. She is an expert in social network analysis.

More lessons from the Virginia Mason Institute – NHS Partnership:

1 Build cultural readiness as the foundation for better QI outcomes

2 Embed QI routines and practices into everyday practice

3 Leaders show the way and light the path for others

4 Relationships aren't a priority, they're a prerequisite

5 Holding each other to account for behaviours, not just outcomes

6 The rule of the golden thread: not all improvement matters in the same way

For more articles on Healthcare and Wellbeing sign up to Core Insights here.

X

X Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn YouTube

YouTube Instagram

Instagram Tiktok

Tiktok